A recent study published in Nature demonstrated that after 44 years, a nodule harvesting site in the CCZ showed mixed recovery signals. The physical impacts from the vehicle tracks and from the missing nodules were still clearly evident. Yet, many of the environmental signals pointed to varying degrees of recovery. Densities for the smaller and more mobile organisms had made a nice comeback while some of the larger and less mobile organisms were just beginning to show signs of return or had not returned at all. Notably, the study showed that in the non-harvested, plume deposition zone, there was no negative impact on abundance and, in fact, higher densities in some larger organisms.

That was the story, and quite honestly the findings weren’t all that notable. They were fairly consistent with past observations, just providing some better definition in certain areas. In fact several years ago, the lead author of the Nature study, Dan Jones, published a meta-study that looked at long-term impacts across multiple sites going back to the 1970’s and noted somewhat similar impacts and recovery observations in many of the observed locations. The new results provide some subtleties that marine biologists find interesting, but there are no obvious policy implications from a study that largely confirms what we already knew.

Yet you wouldn’t know this was the case based on the media coverage. “Deep-sea mining test site shows ‘little sign of life’ 40 years later” read the obviously false headline at Oceanographic. Reuters said, “A strip of the Pacific Ocean seabed that was mined for metals more than 40 years ago has still not recovered… adding weight to calls for a moratorium on all deep-sea mining activity during U.N.-led talks this week.” Louisa Casson of Greenpeace noted that, “This latest evidence makes it even more clear why governments must act now to stop deep sea mining before it ever starts.”

Activists and the media struggle to make sense of studies like this one because they don’t use critical analysis. They evaluate the impacts of DSM in a vacuum rather than next to the activity’s principal alternative, so they are unable to tell whether the results are encouraging or not. Of course that doesn’t stop them from making bold pronouncements, but because their conclusions lack any meaningful context, they are rightfully disregarded.

As we looked at the data and commentary in the Nature paper, we could not find a single recovery path that was clearly worse in the case of a nodule harvesting site after four decades than we experience with terrestrial strip mines over the same or longer periods. For instance, while activists are appalled that harvester tracks remain after 44 years, they seem to forget that the alternative may be removing mountain tops and digging mines that still scar the land after 5,000 years.

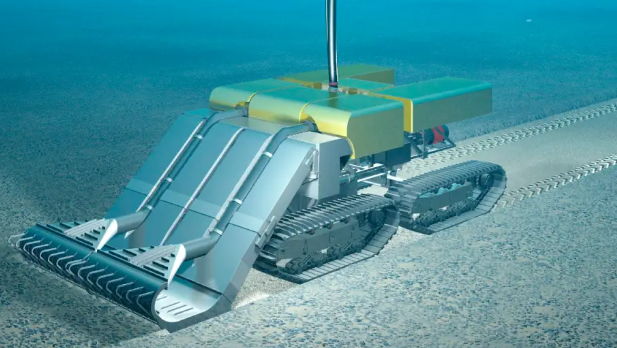

Even when proper land reclamation is practiced after a strip mine is closed, many of the impacts from that mine can persist for thousands of years and longer – changes to biodiversity, soil composition, hydrology, and forestry remain for an indefinite period. These mines often change a region forever. Acid mine drainage from a mine can continue to pollute rivers for thousands of years (link). Studies have shown that deforestation associated with strip mines may increase the area impacted by 12x-28x (link, link). Strip mines often bring people and infrastructure into pristine areas – power plants, processing plants, transmission lines, housing, markets, roads, and rails often accompany a strip mine. Many of those changes are permanent and are far more impactful to a far more sensitive and biodiverse habitat than are collecting nodules, and creating a plume and tracks.

Activists point to the fact that nodules, which provide a hard substrate for some creatures on the abyssal plains, are removed and will not grow back for ten million years or more. Yet strip mines do the same thing with 100x the intensity. A nickel laterite strip mine might yield nickel at 1% grade meaning that we remove 100 tons of ore for processing to yield a ton of mineral product. Nodules grade at essentially 100% so it only takes one ton of ore to yield a ton of mineral product. Both ore bodies – nodules and terrestrial laterites – hold microorganisms, but we need 100x more ore from a strip mine so we kill more organisms and we remove more habitat when we remove that ore from the land. The persistence of the impacts in both cases will span many millions of years, but the scale of a strip mine’s impact vis a vis the ore body must be much larger due to the lower grade present.

In short, the study from Nature confirms the fact that though some impacts from nodule removal will persist for eons, others will recover far more rapidly. In either case, lifting rocks from the bottom of the lightly inhabited and somewhat biodiverse abyssal plains is far superior to clear cutting rainforests and invasively digging underground in the middle of the most biodiverse and endangered ecosystems in the world, where ill-effects can last eons, and where humans will suffer.

TMC holds webcast and presents benthic plume data