Victor Vescovo, a former private equity investor, has been unsuccessfully trolling the deep-sea extraction industry, and TMC in particular, for several years. He has taken his dog and pony show far and wide, desperately seeking an audience who will believe his stories and take his advice.

Yet, Victor has a credibility problem. He has been written off as irrelevant by many of the people who have seen his presentations (with whom we have spoken) and, perhaps more importantly, by the market, which has pushed TMC’s share price higher by ~400% since the start of the year.

Vescovo’s principal arguments – that seabed nodule harvesting is both too risky and too expensive – lack credibility for several reasons:

- If Victor believed his own story, then there would be no need to continue begging people for attention on the subject. An uneconomic industry will simply die under its own weight. Victor’s constant complaining reveals that he has ulterior motives. Given his focus on the government and regulators, our guess is that his real intent is to deceive rule makers with his false logic in order to impose regulatory hurdles on the industry – with the side benefit of protecting another one of his investments. Ironically this effort has backfired on Vescovo, as the Trump administration recognized the market imperfection created by Victor and his merry band of activists and is countering that imperfection with an effort to accelerate the industry’s creation.

- Victor’s interests are quite conflicted when it comes to deep sea extraction, and he does not disclose this conflict anywhere – at least to our knowledge. Victor is invested in a private company, Astroforge, that aims to mine and refine minerals on M-type asteroids. Those M-type asteroids are very high in nickel content and thus Astroforge could be negatively impacted by seabed extraction (which will add to nickel supply). Though Astroforge’s goal is to refine nickel out of its ore and return with platinum metals, at least one independent analyst believes they will be unable to do so, meaning that nickel will be an important mineral for the company.

- Victor is loose with his facts and hypocritical with his application of logic. While he claims that going three miles deep in the ocean to extract nodules is impossibly risky and expensive, in the next breath he says that going millions of miles into space to land on an asteroid, extract minerals, refine them on the asteroid, and then return to earth with the payload is “relatively straightforward” and really, “just a mathematical problem.”

In his latest rant, The Economics of Deep Sea Mining Don’t Add Up, which appears in the online edition of Time Magazine, Victor trots out his tired thesis that TMC is the next Solyndra and is way too risky and uneconomic for investors to consider. It is no wonder that TMC’s investors have been unimpressed. We found Victor’s article so filled with errors and poor logic as to be almost comical. Below we break down each of Victor’s arguments and demonstrate his lack of understanding of the industry. But before delving deep into the Time article, we take an interesting detour to understand Vescovo’s motives and why people find him to be less than credible.

Astroforge

Victor is the proud owner of shares in a private company called Astroforge. And when he isn’t dumping on TMC, he’s pumping Astroforge (see here). While we at COMRC probably know as much about asteroid mining as Victor does about deep sea extraction – after looking at one website and watching a couple YouTube videos – we aren’t dense enough to think that our opinions on asteroid mining warrant a public opinion. Interestingly enough, however, we did find a couple of independent analysts who seem to know a thing or two about space exploration and energy/mining, and surprise of surprises, they believe that Astroforge can never be successful. In fact, one analyst calls Astroforge, “the biggest fraud since Theranos” (see Exposing the $50 Million Asteroid Mining FRAUD! AstroForge).

Now, this post isn’t about lambasting Astroforge. We respect founders who are pushing limits, and maybe Astroforge isn’t the “total fraud” that independent analysts believe it to be (but, wow, it sounds really bad!). This is about Victor Vescovo’s credibility or lack thereof. With that in mind, it’s important to point out that every criticism he makes about TMC and the deep-sea mining industry applies even more strongly—by orders of magnitude—to Astroforge.

For example:

- Vescovo calls deep sea extraction “untried” even though TMC ran a two-month trial where it covered 80+km with a crawler and recovered thousands of tons of nodules and then processed the nodules into commercial products. Astroforge, meanwhile, seems to have “lost” its first two spacecraft to the darkness of space and has demonstrated difficulty maintaining communications and controlling its vehicles after launch. The company has far greater challenges ahead to include landing on an asteroid, extracting hard rock from the surface of that asteroid in micro-gravity conditions, and refining ore on site in deep space. A number of companies have gone before Astroforge, and tried to mine asteroids in the past, but all have failed.

- Victor claims that DSM is very expensive, yet the most recent spacecraft to return ore from an asteroid, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission in 2023, cost $1 billion per kg recovered. Polymetallic nodule harvesting, when scaled, is projected to cost ten to fifteen cents per kg (based on our modeling).

- Victor claims that rare earths are not available from polymetallic nodules in meaningful quantities, but this peer reviewed publication Ore Geology Review notes that nodules in the Cook Islands hold average rare earth grades of 1,670 parts per million or 0.167%. It’s a little awkward that Victor would call 1,670 ppm “not meaningful” when it comes to extracting rocks from 3 miles deep in the ocean, yet he’s willing to back a company that will travel millions of miles into space to mine platinum metals in concentrations of just 225 ppm.

- It probably goes without saying that Victor’s claims that DSM is technically difficult and financially risky are laughable when juxtaposed against his investment in Astroforge.

Victor Vescovo speaks with a forked tongue.

Floundering Arguments in Time Article

Even without considering Vescovo’s revealing stake in Astroforge, Vescovo’s analyses of TMC & deep-sea harvesting leave a lot to be desired. We saw a presentation he made to a group once and quickly picked up on the fact that his numbers related to TMC’s costs were off by several hundred million dollars due to the fact that he had used an incorrect sign preceding a large number. This meant that he had counted that number in the wrong direction which not only rendered his analysis useless but also highlighted Victor’s lack of careful analysis. Yet Victor claims it’s the DSM industry’s economics that don’t add up!

In the Time article, Victor’s first claim is that nodules only yield four metals of economic consequence – cobalt, manganese, nickel, and copper. He leaves out rare earths and titanium which are found in meaningful concentrations in certain geographies, and can be valuable, but Victor got four of the six, so we’ll give him some credit.

He then makes the odd leap to assume that only cobalt and nickel matter because the other metals are plentiful on land. Hold on a second Cap’n Capitalism, you were making the argument about the economic materiality of nodule minerals. You can’t, then, just dismiss the economics of copper and manganese because you claim they are plentiful on land. Yet, with a wave of his magic wand Victor does just that, and eliminates much of the value of a nodule, simply wishing it away. According to Victor’s logic, terrestrial mining companies who produce copper, titanium, manganese, and rare earths might as well close their doors since they have no economic value (maybe if they relocated to asteroids he would find them more appealing).

We can only assume that Victor’s confusion regarding nodule extraction results from his experience with asteroid mining. Since it is so expensive to travel millions of miles into outer space and because payloads are limited, Astroforge must refine platinum metals on the asteroid, concentrating the ore to make it more economic (though there are doubts as to whether this is physically possible). Victor may be incorrectly assuming that likewise, TMC would only recover certain parts of its ore. Yet, TMC isn’t constrained in payload, and it isn’t refining anything at sea. In fact, a big advantage to seabed extraction is that the ore body is mobile (at low cost) from the beginning and can be shipped for processing to jurisdictions where the technology and natural resources are suited for production.

Next, Victor asserts that we don’t need nodule production because “cobalt- and nickel-based batteries are yesterday’s technology.” This thinking is wrong-headed for two reasons.

- Regardless of battery technology and/or the energy transition more broadly, we will continue to need nickel and cobalt production for many decades. It is far better for humanity and the environment if we source these minerals from remote areas with relatively little life and biodiversity in a non-invasive manner than if we invasively take the minerals from areas that are right next to human populations and host high levels of life and biodiversity.

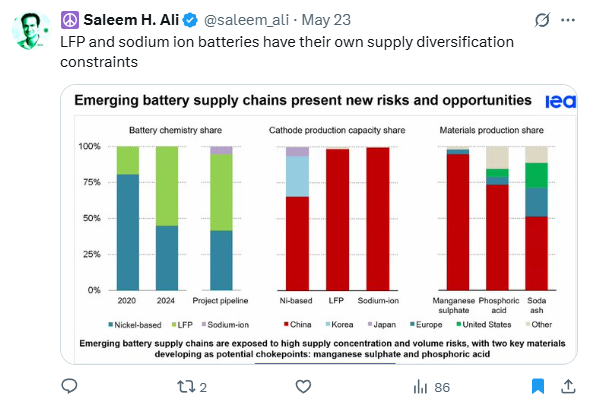

- Victor is completely oblivious to the subtleties involved in battery chemistry production decisions. LFP (lithium iron phosphate) has taken lots of share in the last several years (from nickel-based alternatives) for several reasons, but almost all of those share gains have come in China. China owns most of the refining capacity for LFP components and also controls vast amounts of production IP for LFP cells and packs. The West isn’t opening its arms to Chinese LFP batteries and has imposed tariffs and other controls to make sure that China doesn’t control battery production outside of Chinese vehicles. While Western OEMs are attempting to build out some LFP production, this will take time. Moreover, there are fears of phosphoric acid shortages and some are hesitant to adopt LFP because of concerns around recyclability.

As seen in the chart below, courtesy of Saleem Ali and the IEA, the planned battery investment moving forward shows that nickel-based batteries will be at a level consistent with where they are today. So, if you believe that EVs will grow and that these investments will happen, then there will certainly be greater demand for nickel/cobalt/manganese minerals moving forward than there is currently. Making the false assumption that there is no more need for these ternary metals only serves to reveal an underinformed perspective.

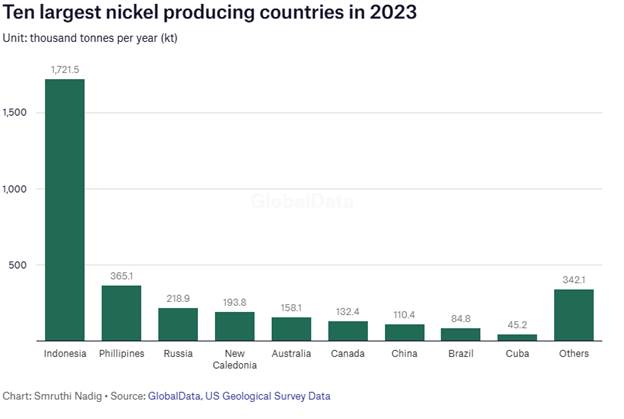

Victor goes on to argue that it isn’t Chinese mining that’s the problem, it’s Chinese processing which creates the issues for the US. Processing is indeed a problem for the US, but Victor ignores the fact that China was smart enough to vertically integrate its mining and processing operations – to insure that it’s processors had reliable feedstock. So, his claims that, “China mines less than 5% of world nickel or cobalt ore, yet they control approximately 75% of nickel and cobalt processing and sales worldwide” are highly deceptive.

China may mine limited quantities of nickel and cobalt within China, but Chinese companies operating overseas have a dominant share of nickel and cobalt production. In the DRC, where most of the world’s cobalt is produced, Chinese companies are known to mine over half of the country’s cobalt and control 80% of output. They also own a large proportion of the cobalt produced in Indonesia (link).

Nickel mining figures are more difficult to obtain because so much of production comes from Indonesia where reporting requirements are not robust, but the government has stated that 90% of nickel mines in the country are under Chinese control. Indonesia now produces more than half of the world’s nickel, and a vast majority of projected supply increases will come from the country. So, Vescovo’s quaint idea that China is simply a processor of energy minerals, and not a producer, is terribly inconsistent with the facts.

Victor proposes that all we need is permitting reform in the US and in allied countries, and our mineral supply chain issues will be solved. “If the United States wanted to secure its own metal supply chains, it would be better to focus on simplified permitting to process critical metals domestically or with our allies… We could do the same with our own allies much more easily and inexpensively than mining the seafloor.” The US is working on permitting reform, and our allies may follow suit, but why would we exclude permitting reform for seafloor resources from the equation? The US has a tough time competing to produce many of these minerals economically from terrestrial resources because we are burdened with high costs and relatively low grades (in many cases). All the same, some projects will be successful, and removing unnecessary regulatory barriers is a great idea.

Yet again, our private equity maven misses the point that if we apply these ideas evenly rather than selectively, and level the playing field to allow capital markets to efficiently allocate resources, the best answer will be produced. Artificially constraining supply (by canceling deep sea extraction) in the face of burgeoning demand doesn’t make sense (well, unless you’re hoping to mine asteroids one day!).

Victor claims that TMC’s cost assumptions, filed with the SEC and made public, are inaccurate. To support his contention (essentially accusing the company of fraud), he cites the fact that the company’s projected costs haven’t changed for several years despite high inflation and an increase in interest rates. Yet, Victor has no idea how much cushion was in TMC’s figures to start, neither does he possess the knowledge or expertise to understand what technologies and methodologies may have emerged over the last several years that work in the opposite direction – to lower costs. Without enough information, Victor’s base case is that he is right and everyone else is wrong (including all public investors and the CFO of TMC – who might have a better command over the firm’s cost structure than Victor). We don’t vouch for TMC’s numbers as we don’t know them well enough. The point is that neither does Victor.

Next Victor asserts it is a “false equivalence” to trade an acre of land mining for an acre of seafloor extraction. He’s onto something here, but he doesn’t have his facts straight. Victor claims that a terrestrial mine yields 564 tons/hectare of nickel due to its three-dimensional nature, while seafloor production only yields 1.5 tons/hectare of nickel. But, he’s simply cherry-picking data to suit his needs. The reality is that assuming an average 15kg/m2 for a nodule harvesting operation yields approximately 150 tons of commercial minerals (in other words, we don’t just count nickel) per hectare. This means that we must use around 3.7x more seafloor to get a ton of commercial metal vs what we use in terrestrial operations (not the 500-2000x that Victor claims). Importantly, our back of the napkin figures match, relatively closely, those arrived at by research analysts who run lifecycle analyses which show around 3.3x more land use in seabed operations (link).

But the story around “false equivalence” doesn’t end there because the deforestation and land-use impacts from terrestrial mining are far greater than in seafloor extraction. In fact, studies show that deforestation from a terrestrial mine will increase a mine’s footprint by 12x to 28x depending on where the mine is located (link and link). So, the reality is that we compromise far more land area to extract an ounce of metal when we take that metal from terrestrial sources than when we take it from the seafloor (we won’t get into plume impacts, but the plumes from a terrestrial mine travel much further than in a seafloor setting).

Victor’s answer to solving for our critical minerals needs is to rely on US production and production by our allies Australia and Canada. But Australia’s nickel production has been cut in half over the last couple of years due to Chinese-backed supply entering the market from Indonesia – making Australian production uneconomic. Canada can help a bit, but Canada will not add enough production over the next several years to meet all of the Western world’s needs. Here’s an idea Victor: why not add low-cost mineral production from the seafloor which also will spare human lives and conserve biodiversity? What’s that you say – it’s not low cost? Then don’t worry about it, those seafloor nodules will not reach the market, and you can go back to asteroid mining! How about we let capital markets do their job, Victor?

Vescovo closes with these final words of wisdom: “Those advocating for deep-seafloor mining are arguing that we need to invest billions in a challenging and untried technology to secure just two metals whose future predicted shortages are now strongly called into question, and by an industry struggling to stay relevant and avoid running out of cash. Support seafloor mining? It could well become this decade’s version of Solyndra.”

Who is the “we” to which you refer, Victor? We’re not suggesting you invest in anything. We’re quite happy to have private investors continue backing the industry. They clearly feel that the technology is less challenging and untested than asteroid mining, BTW.

We don’t know the outcome of seafloor mining because it has yet to happen on a commercial scale, but to try and subvert capital markets and force your clearly wrong-headed and conflicted beliefs in their place is wrong. It’s anti-American, anti-free market, and it’s immoral. It’s also dangerous. Perhaps it’s time to take a step back and reconsider, Victor?

TMC holds webcast and presents benthic plume data